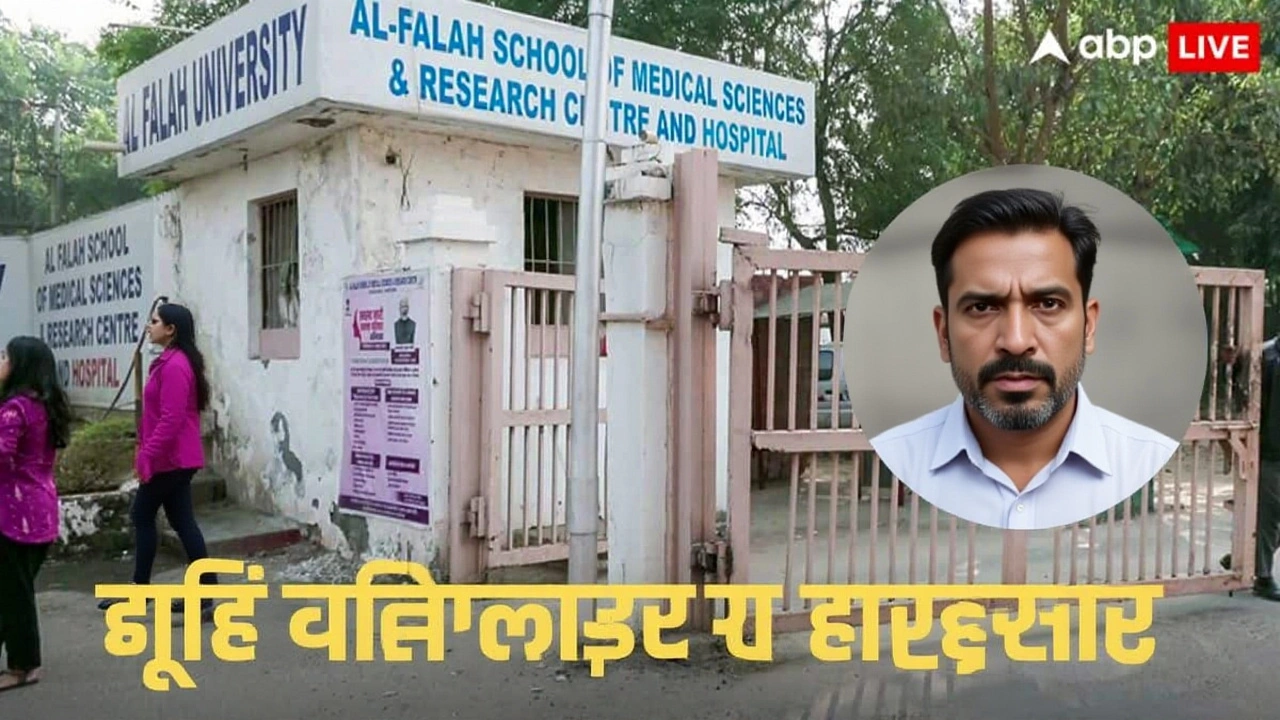

Behind the sterile walls of Al-Falah University’s Tower 17, Room 4 in Faridabad, black smoke had been rising for months — dismissed by staff as faulty ventilation. But after the November 10, 2025, explosion near Delhi’s Red FortDelhi, security guards revealed the chilling truth: Dr. Umar, a faculty member with a medical degree, had been running clandestine chemical experiments in his lab — refining explosive compounds disguised as pharmaceutical research. The discovery, made during a joint probe by India’s National Investigation Agency and Intelligence Bureau, exposed a chilling network of white-collar terrorism tied to the Al-Falah University campus in Dhauj, Faridabad.

From Medical Campus to Terror Lab

The smoke wasn’t just an anomaly. It was a signature. Investigators found traces of ammonium nitrate, acetone peroxide, and ethylene glycol dinitrate — all precursors to high-yield explosives — hidden behind false panels in Dr. Umar’s lab. His notes, recovered from a encrypted server, detailed how he modified detonation thresholds using medical-grade solvents, leveraging his access to university chemistry labs and hospital waste disposal systems. "He didn’t need bombs," said one senior NIA officer. "He needed beakers, Bunsen burners, and a medical license." Dr. Umar, a 34-year-old graduate of the university’s Al-Falah Medical College, had been teaching pharmacology since 2021. Colleagues described him as quiet, meticulous — the kind of professor who never missed a class. But his private movements told another story: frequent overnight trips to Saharanpur, encrypted messages with Dr. Adil Ahmad — arrested in Saharanpur on November 6, 2025 — and unexplained withdrawals from his salary account totaling ₹1.8 million in the six months before the blast.University Denies All Links

In a hastily arranged press conference, Dr. Bhupinder Kaur Anand, Vice Chancellor of Al-Falah University and a practicing MBBS doctor herself, insisted the university had "zero tolerance" for extremism. "We are a 2014-recognized private university with an accredited medical college since 2019," she said. "We have no evidence linking our staff to any unlawful activity." Her statement echoed that of Registrar Prof. M. Parvez, who called media reports "baseless and malicious." But the university’s silence on Dr. Umar’s employment status — he vanished after the Red Fort blast — raised eyebrows. Internal emails, obtained by investigators, show Dr. Umar was still listed as active faculty until November 12, 2025, three days after the explosion.Who Runs the University?

Al-Falah University sits on 70 acres in Dhauj, Faridabad, operated by the Al-Falah Charitable Trust, founded in 1995. It gained university status in 2014 under Haryana’s private university law — a legal loophole that granted it autonomy over admissions, faculty hiring, and fee structures. Unlike public institutions, it answers to no state education board. Its medical college, with 650 beds and MRI/CT facilities, is run by Dr. Bhupinder Kaur Anand, who also chairs the college committee. The dean of academics, Dr. Mehra Singh Puniya, and the medical superintendent, Dr. Lakhi Ram Murmu, have yet to comment publicly.Recruitment Patterns and Suspicious Hires

The investigation uncovered a troubling pattern: over 68% of new hires in the medical and engineering departments since 2018 came from Jammu and Kashmir — often on salaries 40% below market rate. "They weren’t hired for their credentials," said a senior Home Ministry source. "They were hired for their connections." One former lab technician, who spoke on condition of anonymity, recalled being asked to "ignore odd shipments" arriving at the university’s chemistry wing. "They came in labeled as ‘medical kits’ — but the weight didn’t match the contents. We were told not to ask questions." The university’s admissions office, meanwhile, accepted over 1,200 students in 2024 alone — collecting ₹415 crore in fees. Yet, only 37% of that revenue was accounted for in infrastructure upgrades. The rest, according to income tax raids, flowed into shell companies linked to Jawad Ahmad Siddiqui, who registered a foundation called Tariqiyah in 2012 on land near a Delhi crematorium — a known hub for covert financial activity.

Students Caught in the Crossfire

For the 50+ students from Saharanpur who fled the campus after the blast, the nightmare is just beginning. Fifteen medical students and twenty engineering students have dropped out, returning home with no transcripts, no exams, and no clarity on whether their degrees will ever be recognized. "We paid ₹8 lakh each for a 5.5-year MBBS course," said Ayesha Khan, a third-year student. "Now we’re being told our university might be shut down. What happens to our NEET eligibility? Our future?" The July 2025 results, once scheduled for release, remain frozen. The university’s website now displays a single line: "Academic activities under review."Why This Matters

This isn’t just about one lab or one professor. It’s about how institutions meant to uplift marginalized communities can be weaponized from within. Al-Falah University was once seen as a beacon — a cheaper, closer alternative to Jamia Millia Islamia for Muslim students in the National Capital Region. Now, it’s a cautionary tale: autonomy without accountability breeds vulnerability. And when education becomes a cover for terror, everyone pays the price.Frequently Asked Questions

How did Dr. Umar access explosive materials in a medical university?

Dr. Umar exploited the university’s lax oversight of chemistry labs and medical waste disposal. He used hospital-grade solvents like acetone and ethanol — legally available in labs — and combined them with ammonium nitrate, which he reportedly obtained through fake procurement orders under the guise of "research chemicals." His medical license gave him access to restricted areas, and his quiet demeanor helped him avoid suspicion.

Why is Al-Falah University under special scrutiny?

As a minority institution, Al-Falah University operates with significant autonomy under Haryana’s private university law, allowing it to bypass standard audits for faculty hiring and fee structures. Investigators found irregularities in its financial flows, with ₹415 crore collected from students but unaccounted for in infrastructure. Its recruitment of over 68% staff from Jammu and Kashmir, often on below-market pay, raised red flags about potential infiltration.

What’s the status of the students affected by the closure?

Over 50 students from Saharanpur have left campus, with medical and engineering students most affected. Their academic records are frozen, and the university has not confirmed whether their degrees will remain valid if the institution loses accreditation. The University Grants Commission (UGC) has initiated a special audit, but no timeline has been given. Students fear their years of study and ₹8 lakh fees may be lost.

Is Al-Falah University’s accreditation at risk?

Yes. The UGC has placed the university under special review, and the National Assessment and Accreditation Council (NAAC) has suspended its "A" grade status pending investigation. If the university is found to have knowingly harbored terrorist activity or misused funds, its recognition could be revoked — invalidating degrees awarded since 2019. The Ministry of Education is now considering a takeover by a government-appointed administrator.

What role did Jawad Ahmad Siddiqui play in this case?

Jawad Ahmad Siddiqui, founder of the Tariqiyah Foundation, registered in 2012 on Delhi’s crematorium land, is suspected of funneling illicit funds into Al-Falah University. Investigators believe the foundation served as a front to launder money collected from student fees, which then financed the terror module’s operations. His name appears in bank transfers linked to Dr. Umar’s accounts and the Saharanpur arrest.

Could this happen at other minority universities?

Experts warn it’s possible. Over 120 private minority universities in India operate with limited financial transparency. Many rely on state exemptions to avoid audits. The Al-Falah case has triggered calls for mandatory third-party audits, public disclosure of faculty backgrounds, and real-time tracking of lab chemical inventories — especially in institutions with high enrollment from conflict-affected regions.